In September 1996, I came to Rotterdam to participate in the Dutch Electronic Art Festival – not as an artist yet but as a film curator, or, to say it better, as a film curator from Moscow who made a website for a film club. For many people, the mid-90s were all about going online, making websites, travelling to the East and to the West.[1]

It was my very first media art event. I was overwhelmed by the scope and scale of the interactive installations – the huge, loud constructions of Knowbotic Research; the scary performances of half-human, half-cyborg Stelarc; the trips in a virtual submarine that seemed so real, and other interactive and immersive stuff distributed throughout the city. The modern architecture of Rotterdam was truly enhanced by all of these futuristic objects with their surprises inside.

One of them – an inflatable internet café floating on a canal in Rotterdam’s centre – left a strong impression on me. I kept thinking about it and talking about it over the years. After all, it was the first thing I saw as I headed from the railway station to the DEAF offices, and it was so different from any other previous experiences I’d had with the internet in public spaces. I had never been to a “normal” internet café before and suddenly I found myself in this totally over-the-top place.

Well, years later I found out that it was not really an internet café but an “an intelligent object,” an “inflatable sculpture with brains connected to the World Wide Web”[2] called ParaSITE and built by the Dutch architect Kas Oosterhuis and his team.

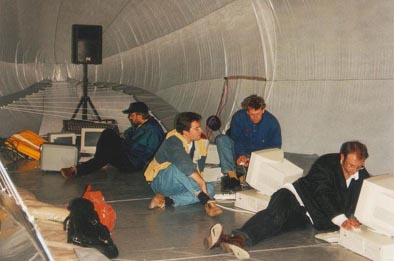

After I squeezed inside through the tight soft gates, I found myself in a space that can probably best be described as the inside of a spaceship or other apparatus designed to take you into outer space. Stylish pillows wrapped in plastic invited you to make yourself comfortable and situate yourself behind the connected computers. As well as check your email — for free.

The place was crowded. People were reading and writing emails, looking up the URLs they had recently received from other festival venues on business cards and pieces of paper. Everyone really enjoyed the atmosphere there.

The festival’s participants would no doubt have enjoyed being online in more trivial situations. They would have happily rushed to the computers even if they hadn’t been installed inside this zeppelin-like bubble. The extraterrestrial beeps and blinks it was producing were not the reason why people were coming and staying inside. But still, it felt very right that the internet-connected PCs had a special space constructed just for them in a special location. After all accessing a mail server is not nearly as exciting as entering the CAVE. Opening a page in a browser can’t be compared to the spectacular act of manipulating Stelarc through electronic impulses. On the other hand, the notion that there was something bigger happening right now was in the air. The interactive monsters of the day were just about to become obsolete, making way for bigger and more important things, namely, the World Wide Web.

Back then, going online and just being online were the thing to do. Networking was the passcode into the new millennium. And we, people on the web, even those who just had started to make their own pages, would fly into it soon to become human apparatuses like that gorgeous zeppelin moored on the channel in Westersingel street.

I came back to Rotterdam in October 2010 with an exciting new challenge from the research program at the Willem de Kooning Academy – to write about Rotterdam’s internet cafés. After years of working online, researching the vernacular web and digital folklore, I was about to begin my investigations of the “low forms” of digital culture in real life.

From my window in my Goethe Institute apartment on the Westersingel, I could see the canal, but, of course, ParaSITE was long gone and, I should add, along with it, all of that mid-90s excitement about the Web as well. But this kind of statement doesn’t really begin to capture what has actually happened since then.

Over the past one-and-a-half decades, the internet has experienced its ups and downs, the WWW has been kissed goodbye and welcomed back a number of times. And as I write this, it has again disappeared from the centre of media attention. In fact, in August 2010, Wired declared the web dead again, with its editor-in-chief casually observing that “The Web is not the culmination of digital revolution.”

[3]

Ironically, the next big thing according to Wired is all about interactivity, just like in the early 90s. Only this time, the focus has been narrowed down to the interactions that people have with that one particular mobile device that you can touch and shake. The New Media world is totally preoccupied with imagining and testing new apps for mobile phones. This made it an interesting time for me to commence with my research, just as the spiral of technological evolution was making yet another new turn, bringing a certain completeness to the entire period before it, which gives us an opportunity to highlight it and analyse the phenomena that are still there, but already belong to another era.

Among them are the internet cafés, places you won’t need to visit if you are equipped according to modern standards. And users are fleeing the number one Dutch social network, Hyves, for the seemingly cleaner and better organized Facebook, marking another endpoint of the web’s diversity and decentralisation.

In the mean time, Geocities, millions of home pages created over the past 15 years, was officially shut down by Yahoo in 2009, but was quickly rescued by a group of underground archivists who made it public again in late 2010. Both, Geocities’ destruction and the resurrection, are significant events for web culture.

I’ve been buying connection time in various Rotterdam belhuizen (Dutch for “call shop”), browsing through Hyves user profiles, analyzing Geocities pages, to find myself amongst the ruins of the Web that I believe was a culmination of the digital revolution.

Rotterdam, 2011 - 2012